The Hon Sir Steven Runciman CH FBA 1903-2000

Faced by the mountainous heap of the minutiae of knowledge and awed by the watchful severity of his colleagues, the modern historian too often takes refuge in learned articles or narrowly specialized dissertations, small fortresses that are easy to defend from attack.

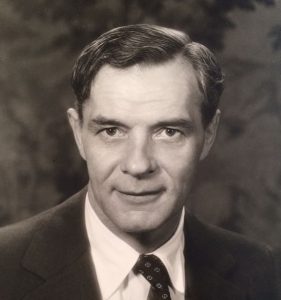

Steven Runciman

George Jellicoe (Earl Jellicoe, son of Admiral Jellicoe of Jutland fame) was a close friend of Steven Runciman. It was he who, as Chairman of the Anglo-Hellenic League, instituted the Runciman Award which was first awarded in 1986. He published the following tribute to Sir Steven in The Anglo-Hellenic Review in 2001:

Sir Steven Runciman, who died aged 97 on November 1 last year, was a man of many parts: an eminent scholar and historian, responsible in no small measure for the revival in the 20th century of our western interest in Byzantine history and art, a leading authority on the Crusades, a traveller and lecturer world-wide and, above all, a fascinating if somewhat mysterious personality with an address book second to none of his many friends across the globe, containing as it did an A to Z of the world’s royal, distinguished and influential families.

Born in July 1903, he was the second son of a leading Liberal MP, Walter Runciman, later 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford, who with his wife, born Hilda Stevenson, were the first married couple to sit together in the House of Commons and who was a member of Asquith’s Cabinet in the First World War. Steven’s grandfather, also a Walter Runciman, founded the successful Runciman shipping business.

His high intelligence manifested itself at a very early stage in his life, starting to learn French at the age of three, Latin and Greek at seven and Russian at eleven. It was not surprising, therefore, that he won a scholarship at Eton where his life-long capacity for friendship quickly manifested itself – his friends including ‘Puffin’ Asquith to whose father, then Prime Minister, he owed an invitation to stay at No. 10 in 1916. His health, however, then as later, was delicate and many of his Eton days were spent at home which, given his taste for reading, learning languages and, above all, history, he put to good use.

He went up to Cambridge in 1921 as History Scholar at Trinity, his father’s old college, and began there an association with Trinity which lasted all his life. His rooms there were unlike those of most undergraduates, furnished and decorated as they were in the very special Steven taste. His life, as always, was extremely social, his circle at that time including Dadie Rylands, Cecil Beaton, John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey and, above all, Noel Annan who remained until his recent death a particularly close and highly esteemed friend. His fascination with history, especially medieval history and that of Byzantium, never lapsed and he graduated with a First in History in 1924.

After graduation he was keen to continue with Byzantine research. Luckily for him the Regius Professor of History at Cambridge was Professor J. B. Bury, a rare bird at that time in that he was a specialist in Byzantine studies, then a neglected subject. Bury, however, was not keen to take on more pupils and it was only by waylaying him on his daily walk through the Backs that Steven was able to contact and interest him. This led to his dissertation on Romanus Lecapenus, the 10th-century Byzantine Emperor, which earned him his Fellowship at Trinity in 1927, was published in 1929 and was followed by two further volumes: The First Bulgarian Empire in 1930 and a fine book, Byzantine Civilisation, in 1933.

The travelling scholar

At that time, and the same was the case until his death, he travelled extensively. In 1924 he made his first visit to Greece and Istanbul in the family’s great yacht The Sunbeam. In 1925 he visited China, helping the ex-Emperor, Henry Pu Yi, to improve his piano playing. Thereafter he travelled widely, often by mule or by foot, throughout Greece, where he became and remained a close friend of George Seferis, later a Nobel Poet Laureate. he also spent no little time in Serbia, Moldavia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Jerusalem and Siam, with whose Royal Family he had formed close connections.

In 1938 having inherited a goodly fortune from his grandfather, he accepted the advice of George Trevelyan that if he wished to concentrate on writing he should resign his Fellowship at Trinity. When war broke out, being unfit for military service, he was appointed, on the recommendation of his former pupil, Guy Burgess, Press Attaché in Sofia, where he remained until the German advance into Bulgaria in 1941 when, after evacuation to Istanbul, he was lucky to escape death from a explosive device. Thereafter he served for the Ministry of Information in Cairo and, most happily, in Jerusalem until in 1942 he was appointed, at the request of President Inönü, Attaturk’s successor, and on the recommendation of another old Trinity friend Michael Grant, Professor of Byzantine Art and History at Istanbul University. This was indeed the only university at which he ever held a chair and he relished his full and socially active years in Istanbul where he could devote his spare time to Byzantine and Crusader research, where he became an Honorary Whirling Dervish and where the Italian Embassy in a report labelled him ‘molto intelligente, molto pericoloso.’ On this his old friend Professor Bryer has I think rightly commented: ‘If Runciman had been a spy, he would have made a better story of it!’

After the war, from 1945-1947, he was the highly-regarded British Council representative in Athens where he worked closely with Osbert Lancaster and with Patrick Leigh Fermor, another close friend whom he had first met at a Byzantine Conference in Sofia in 1934. I doubt whether the British Council has ever had a better or more influential representative in the Athens which meant so much to him, where he was so popular in all ranks of Athenian society including King George II of the Hellenes, whose fortune he used to tell.

Literary achievements

On returning home he based himself on his pleasant house in St John’s Wood and on the island of Eigg which he shared with his brother. He devoted himself mainly to his books on history and art, above all of the Byzantine period, and on the Orthodox faith. However he also travelled widely and gave many lectures around the world. These could be very taxing. For example, on one of his five visits to Australia he gave no fewer than 20 lectures and presided over ten seminars; and in the United States his lectures ranged across the whole country, from the east coast to Los Angeles in the west and north to Alaska. In addition, of course, he always gave much time and attention to his innumerable friends.

Apart from numerous article his major post-war books were: The Medieval Manichee (1947), A History of the Crusades (3 volumes, 1951-54), The Eastern Schism (1955), The Sicilian Vespers (1958), The White Rajahs (1960), The Fall of Constantinople 1453 (1965), The Great Church in Captivity (1968), The Last Byzantine Renaissance (1970), Byzantine Style and Civilisation (1975), Mistra (1980) and A Traveller’s Alphabet, Partial Memoirs (1991).

I confess that I have not read all this considerable literary output. However I have read quite a few of his books and always with interest, enthusiasm and admiration. These include perhaps his greatest work, The History of the Crusades, the intensely moving The Fall of Constantinople which, once opened, is impossible to put down, the fascinating Sicilian Vespers and that charming short volume, Mistra. I agree with Steven’s dictum that: ‘the supreme duty of the historian is to write history, that is to say, the attempt to record in one sweeping sequence the greater events and movements that have swayed the destinies of man.’ And this our author has done superbly well in those memorable books. I also agree with Gore Vidal’s judgement on The Fall of Constantinople, namely that ‘he tells his story plain. Since God has not revealed any master plan to him, he does not feel impelled to preach “Truth to us”. He does make judgements but only after he has made his case. He likes a fact and distrusts a theory and is always pleasurable to read.’ As Gore Vidal states: ‘To read a historian like Runciman is to be reminded that history is a literary art quite equal to that of the novel.’

In 1966 Steven, after the sale of Eigg, moved to Elshieshields, a fine peel tower in Dumfriesshire. It was a pleasure to stay with him in that charming property full of his treasured possessions and with his fine collection of paintings by his Scottish ancestor, Alexander Runciman, and his 40 Edward Lear watercolours. Scotland meant much to him and from Elshieshields he journeyed, health permitting, frequently to Edinburgh, giving much attention to the National Trust for Scotland, to the Scottish Museum of Antiquities and to the Scottish Ballet. Likewise, on his trips to London, staying in his later days at the Athenaeum, he occupied himself, in addition to his intense social life, with his responsibilities as a Fellow of the British Academy, a Trustee of the British Museum, a Member of the Advisory Council of the Victoria and Albert Museum, as Vice-President of the Royal Historical Society and as a most active Vice-President of the London Library.

In his Partial Memoirs he states that ‘Greece is to me a second country’. He served for 16 years (1951-67) as a very special and particularly effective Chairman of the Anglo-Hellenic League – ‘The Anglo-Hell’ as he liked to term it. It is not surprising that the Annual Runciman Award for the best books on Greece in English and the Annual Runciman Lecture should have made such a mark. It owes much to him and to the fact that, unless health ruled his attendance out, he was always present at the Award ceremonies.

Sir Steven and Mount Athos

In the later years of his life he took a very particular interest in Mount Athos which he had first visited in June 1937, becoming the first President of the Friends of Mount Athos in 1990. In 1997, when awarded the Onassis Foundation’s massive prize for culture he decided, with typical generosity, to finance the conservation of the Protaton Tower at Karyes at a great ceremony there in July last year. In his speech he spoke of his first visit and how he had been struck by the beauty of Mount Athos which, to quote his words: ‘remains in my experience the loveliest piece of scenery in all the universe.’ And, very typically, that address was given in fine, ecclesiastical Greek.

His life on earth in fact came to a peaceful end only four months later, while staying with a greatly-loved great nephew in Warwickshire.

Sir Steven rightly received many honours. He became a Fellow of the British Academy in 1957 and was also a Fellow of many universities here and abroad. He was knighted in 1958, received the Greek Order of the Phoenix in 1961 and was appointed a Companion of Honour in 1984. A recognition which meant particularly much to him was his appointment by his friend, the Oecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras, as Grand Orator of the Greek Church – an appointment which, he said, would have allowed him in the good old Ottoman days to bear the hereditary title of Prince.

Lord Jellicoe

The Anglo-Hellenic Review, No 23, Spring 2001